- Home

- Jackie Hirtz

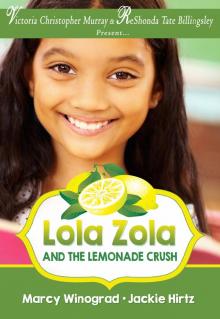

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush Page 10

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush Read online

Page 10

“Stop it! Leave him alone,” she shouted.

Rolling down the window, Mr. Wembly said innocently. “We’re just having a father-son chat. No need to worry.”

“I am worried,” said Lola. Peeking her head through the half-open window, she said to Buck, “Don’t let him talk to you like that.”

Furious at Lola for interfering in a family affair, Mr. Wembly jerked open the car door, jumped to his feet, and faced Lola.

“Young lady, this is between my son and me.”

Yuk! Mr. Wembly’s breath was gross. What was that odor? Whiskey? It sure wasn’t lemonade. No wonder the guy wore so much cologne.

“No, it’s not just between you and your son,” said Lola. “It’s between you and everyone else in Lemonade Gulch.” Lola looked over at the strikers who had stopped picketing; at the lemonade drinkers who had stopped sipping; at Aunt Liza leaning against her motorcycle; at Ruby Rhubarb, who was rooting for Lola, making a “right on” sign with her raised fist; at her parents looking out their kitchen window, no doubt arguing about whether they should have joined Melanie on the picket line. “We heard every word,” said Lola.

Stunned, Mr. Wembly glanced at the screen on the dashboard. The light for the PA system was on. Trying to compose himself, he cleared his throat, turned off the PA, and said quietly, “It’s off. Now run along, little girl.”

“I am not a little girl,” said Lola with an air of authority. She looked at Mr. Wembly, who stood with his arms crossed. His breath was worse than Bowzer’s breath after a rat snack. Lola stepped forward, sandwiching herself between Mr. Wembly and the car door.

“Buck, are you okay in there?” she asked, trying to see through the window.

“Move out of my way, little girl,” said Buck’s father, eager to climb back into the limo and take off. “We’re going home to finish our ‘private’ conversation.”

“No we’re not,” said Buck, bolting out of the limo. “I never want to go home. I hate you, Dad,” he shouted as he tore off, purposely bumping into the buffet table and knocking over a couple of the Wemblys’ expensive crystal pitchers. He ran down the street in his white suit and derby hat, not looking back once at the shattered glass, his father, Lola, or those who ached for him. “You’ll be sorry,” he yelled, holding onto his hat with a trembling hand.

“See what you did,” said Buck’s father, shaking his head in disgust at the broken pitchers in the street. “He’s run away before, huffs and puffs a few blocks, then comes back and apologizes. My son is a little mixed up. He needs to grow up. One day he’ll take over Boingo Bits. This is just a glitch in the wheel.”

“I think he means a nail in the oven,” Melanie whispered to Lola.

“That would be nail in the coffin,” said Lola, “but that’s not what’s happening here.” She turned to Mr. Wembly, changing her tone to grown-up firm. “You’re a mixed-up bully,” said Lola, “and by the way, your breath needs a major bath.”

With Buck still in sight and about to turn the corner at the end of Salt Flat Road, Lola beat her feet against the black asphalt, giving chase in her red tennis shoes, and praying to the Spaghetti God not to turn her lanky legs into feeble noodles. Lola was usually marathon material, but the sun was so chili-pepper hot, she thought she might faint from heat exhaustion.

She saw Buck make a right turn at the corner, then a left at the traffic light, then what? Where did he go? Oh, there he was, sprinting through the sleepy business district, past the Mirage Twin Cinemas, past Mrs. Garcia’s dress shop, past stop signs, nearly getting hit by a car. Same for Lola, who was only thirty yards, twenty yards, ten yards behind him, calling out to him.

“Buck, stop! Talk to me. Please.”

But Buck didn’t stop or talk or even turn back to look at Lola. He just kept on running until he reached his father’s two-story glass office building with the life-size clay sculptures of athletes, toy chests, and cartoon characters sitting on top of the roof. Once there, Buck punched in a secret code, which Lola might have seen if a monster moving van hadn’t roared up just as she was about to cross the street and catch up with Buck.

“Darn it,” mumbled Lola, standing in front of a locked glass door. How would she ever catch up with him now? What was he doing in there anyway? And who knew the secret code to get in? Furrowing her eyebrows, Lola searched her brain bucket for a possible code. She had heard Buck talk about how his father changed the security code at least once a month so that no one outside the company could sneak in and steal its software secrets, or put a virus in an about-to-be-released, brand-new video game.

During a lesson in Mrs. Rosenberg’s class, Buck had let it slip that the codes were always four or five digits and that some of the old codes were words that had been reversed or scrambled. When Mr. Wembly was working on a new Superpower video game, the entrance code had been laser spelled backwards, resal. Just before Buck’s father published a ping-pong simulation video game, the code had been ping with a p at the end of ing. The possibilities were as numerous as Melanie’s freckle potential.

Since Mr. Wembly was about to publish the basketball simulation video starring The Rising Sun, Lola experimented with words such as hoop, shot, Sonny Wilkerson, foul, team—frantically punching in the words spelled forwards and backwards, and with the letters reversed, but to no avail. The front door didn’t budge. What in the world was Buck doing inside the building by himself? She understood why he would want to run away, but couldn’t imagine why he would run to his father’s office, unless he wanted revenge and hoped to hurt his father as deeply as his father had hurt him.

“I guess I’m just a lemon,” were the words he used when his father ranted and raved in the Cadillac. He didn’t mean a lemon as in the fruit, or lemon as in “bad bozo mobile.” He meant lemon as in loser—a boy who will never amount to anything, a son who only disappoints his father. Strange how that word kept popping up. Lemon. Isn’t that the word her mother was about to say when she tried to tell Lola the secret code? It wasn’t lemonade her mother had said. It was…

Lemon, lemon, lemon, the word did somersaults in her head. Lola figured the secret code was trying to tell her something, so she punched the letters l-e-m-o-n into the keypad and waited, her heart pounding, please, please, please, open sesame. Before she mumbled, “I can’t believe it!” she was inside the building, racing up the stairs to the second floor, where she could hear someone (Was it Mr. Wembly? Had he beaten her to the punch?) talking, and someone else walking, no, stomping around, and dropping things. Ka-boom!

“Buck, what are you doing?” said Lola, once she reached the top of the stairs and almost tripped over a mountain of papers scattered on the floor. Buck was emptying every file cabinet in sight, hurling folders of documents at a giant screens featuring Mr. Wembly in a promotional video cheerfully pitching his latest video games to retailers. The office, full of metal file cabinets, drafting tables and computer terminals, looked like it had just been hit by an earthquake. Desk drawers were pulled out and their contents dumped, wastepaper baskets sat upside down, and chairs lay on their sides.

“I told him he’d be sorry,” said Buck, throwing a folder at one of the screens.

Lola stood there watching, speechless. She felt as though she was in a movie, and not a G-rated classic like Lawrence of Arabia, but a disturbing drama rated R for “rebel.”

Buck sat down at his dad’s desk and logged on to a computer. On the large screen behind Buck, Mr. Wembly was talking up his new family entertainment package.

“Buck, this mess isn’t going to prove anything to your father,” Lola said, picking up a drawer and putting it back where it belonged.

“It’ll prove I’m not a sissy,” said Buck, staring at an animated computer graphic of The Rising Sun in front of him.

“It’ll just prove that you’re bonkers,” Lola said, wondering what Buck was up to now.

“Like he is,” said Buck, substituting the image of his father for that of The Rising Sun and making it literally i

mpossible for anyone playing the game to score points. Buck deleted the “You scored” message and typed in “You’re drunk.”

Lola walked over and read the message. “That’s not funny, Buck.”

“It’s not supposed to be funny.”

“What’s it supposed to be then?”

“A surprise. No one’s gonna have a clue until…”

“Until what?”

“It’s too late and the game is in the stores or downloaded.”

“And little kids are reading a ‘you’re drunk’ message every time they shoot a basket? What kind of message is that?

Mesmerized, Buck replaced commands and messages, screwing up his father’s new product big time.

Lola sat down in a swivel chair next to Buck, trying to get him to pay attention to her. “Don’t do this,” she implored, swiveling in a complete circle. Buck ignored her. She might as well have been a gnat, except there weren’t any bugs in this clean, sterile office. Lola tugged at Buck’s suit sleeve, but he brushed her away so she ripped the derby off his head, sent it whirling Frisbee-style across the room, and repeated, “Don’t do this!”

“I’m doing it,” he whispered without flinching, typing in one command after another, making the “You’re drunk” message light up in different colors. Blue, green, red.

“It’s not right,” said Lola.

“Then how come it feels better than riding a mountain bike?” said Buck.

“Because you’ve never stood up to your father before.”

“Because I’m a lemon.”

“Because you had lockjaw,” said Lola, “and you still do.”

Buck stopped typing and stared at the monitor, avoiding Lola’s eyes. “There are many different ways to communicate. This is one of them,” said Buck.

“If you want to stand up to your father, tell him how you feel. Don’t sneak behind his back, ruin his new game, and scare little kids.”

“I can’t talk to him. It’s like talking to an army general. All you can say is yes sir, no sir.”

“You can do it.”

Buck logged off the computer, stood up, and headed for the stairs.

Lola was about to go after him, but thought better of it. Boys didn’t like to be chased. Lola, the human glue stick, stuck to her seat, mid-swivel.

“Where ya going?” she asked.

“Away,” said Buck, staring out a window, gazing at the sandy landscape. Lola imagined him trudging through the desert, picking cactus needles off his socks, talking to tumbleweeds, living off California dates and prickly pears. The Buck in her daydream was caught in a sandstorm when the real Buck, the one mumbling by the window, jolted her from her fantasy.

“I’m going far away,” said Buck, hitting the Off button on the remote control to the big screen. “Bye, Dad,” he said with a click of bitterness.

What about me, thought Lola, trying hard to swallow the lump in her throat. Impossible. It was the size of a tablespoon of peanut butter. Lola wondered, “Aren’t you going to say good-bye to your friend?”

Apparently not, at least not with a traditional wave, hug, or “It’s been great knowing you and your wacky hair bows.”

“By the way, you’re not so bad for a girl,” Buck said, turning to Lola before descending the stairs. Seconds later, he added, “You can have my synthetic cow eyeball. I won’t be sticking around to dissect it.”

Leaping up from the chair, Lola ran to the stairwell and called out to Buck, “I don’t want your sticky fake cow eyeball. I want you to stick around. Stay here!”

“Here, here, here,” the word echoed inside the stairwell.

At the bottom of the stairs, Buck stopped, took a deep breath, then crumpled like a piece of paper.

“I can’t go home,” he said. “Not yet.”

Lola could understand that. If she had a father like Mr. Whiskey Breath, she wouldn’t want to go home either, at least not before cranking up some serious courage. She figured the best place for Buck to find his warrior soul was in her backyard.

“Buck, come on over to my house. We can powwow in my teepee. It’s really cool.”

Buck paused for a long time, longer than it takes for Melanie to squeeze the juice out of a lemon. Why was it taking him forever to answer? Lola would be old, maybe thirty, before Buck made up his mind.

“Okay,” he said, hesitantly.

Lola wanted to jump out of her epidermis, but acted like the queen of cool.

“First, we’ve got to make like genies and zap this place clean,” she said.

Buck climbed back up the stairs, reluctantly. “All right, Lola Zola.”

Together, Lola and Buck straightened chairs, collected loose papers, put back files, and did their best to restore the office to its pre-Buckquake condition.

With a little more prodding from Lola, Buck deleted the “You’re drunk” message and restored it to “You scored” on the new video game software.

Then, as dusk turned to night, they made like buffalos and charged across town, back to Salt Flat Road, where Lola knew her worried parents would be waiting for her, wondering if they should call the police or talk tails with Bowzer until their daughter returned home.

*** *** ***

Chapter 12

“Let me do the talking,” said Lola, as she and Buck sprinted across the Zolas’ front yard, a white-pebble, water-conserving landscape, and approached the “Casa Bella” sign on the door of the stucco house.

“You’re not the only one who can talk. My mouth moves too,” said Buck, out of breath and out of sync with Lola’s” I’m in charge” attitude.

“Just let me explain what happened,” insisted Lola, catching her breath, about to knock on the door. Before Lola had time to knock, however, the front door swung open.

“Your father and I have been worried sick about you two,” said Diane Zola, putting her arms around Lola and Buck and leading them into the living room.

Bowzer bounced off the Slinky-popping sofa and purred as he wove around Lola’s and Buck’s legs.

“You almost gave me an ulcer,” said Bowzer in his baritone voice, the voice that only Lola could hear. “I didn’t eat one morsel of tuna while you were gone. I even passed on the poultry.”

From the kitchen came the smell of sizzling onions and chicken. Lola’s mother had been cooking burritos, figuring that maybe if she prepared dinner, someone, someone like her daughter, might show up in time to scarf it down.

Lola’s stomach made like a lion and roared for a home-cooked meal. No wonder she was starving. She hadn’t eaten all day, and the chili peppers in the lemonade had burned a humungous hunger hole in her tummy. Bowzer, secure in the knowledge that Lola was back, tiptoed over to his bowl and devoured every crumb of what he usually considered boring dry food.

“We drove all over town looking for you,” said Diane Zola, emerging from the kitchen. “Where have you two fugitives been?”

Lola and Buck exchanged “You explain it” looks. Finally, Lola said, “Shooting basketballs.”

“Well, thank goodness you’re back,” said Diane Zola, wiping her hands on her apron and planting a kiss on Lola’s cheek. Bowzer meowed for affection, so Lola leaned down, picked him up, and planted a small kiss on his head.

“Buck, your father’s been calling, wanting to know if we’ve heard from you,” said Michael Zola. “I think you better call him on the parrot phone.”

“I’ll call him after Lola shows me the teepee,” said Buck, wanting his father to suffer a little longer. Buck had never run away for more than an hour. It was seven o’clock now, four hours since he had bolted from the limo.

“You can’t have a powwow on an empty stomach,” said Lola’s mom. “Pack some dinner snacks.”

Stuffing her backpack full of burritos, grabbing her MP3 player, and handing Buck a pitcher of her lemonade, Lola escorted her old-foe-new-friend to the backyard, where hidden behind the rose bushes and cactus garden sat a sheet and a tree-branch teepee. Her father had pieced it to

gether after a thunderstorm ruined the one he gave her for her seventh birthday.

Crawling inside the teepee, Buck almost spilled the lemonade all over his suit, but Lola caught the pitcher mid-wobble. She could hear Bowzer, who had been tagging along, thinking, “That’s one nervous kid.” Lola could hear Bowzer’s thoughts—most of the time, anyway.

Maybe some Andean vibes will make Buck feel better, thought Lola. She flipped on some music she had bought at the Unity Center, and imagined, just for a moment, that they sat on a mountain in Peru, listening to the llamas play the flutes.

Sitting down cross-legged, the two stared at Bowzer’s missing tail, each one waiting for the other to break the ice. Growing impatient, Lola broke a burrito instead and passed half of it to Buck. It wasn’t a peace pipe, but it might be a truce trigger.

“Why are you being so nice to me?” Buck asked suspiciously, before taking his first bite.

Bowzer, sitting in Lola’s lap, eyed the untouched appetizer and wondered if he should pounce.

“I’m tired of competing with you,” said Lola, taking a bite of burrito.

“You really mean that?”

Lola nodded enthusiastically, not just because she meant what she said, but because her mouth was on fire. Apparently Mom had found the chili peppers and tucked them neatly into the burritos.

“Thanks for sticking up for me,” said Buck. “No one’s ever done that before.”

“No biggie.”

“Yes, biggie.”

“Tell me something, Buck,” said Lola, taking three huge swigs of lemonade to quench the fire.”

“Forget it. You can’t have the combination to the lock on my mountain bike.”

Wake up, Slime, thought Lola. She already knew the combination. Ms. James Bond had spied him opening the lock several times and jotted down the combination on her sweaty palm. No, that wasn’t what Lola wanted to know.

“Why did you open a lemonade stand right across the street from me?” she asked.

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush