- Home

- Jackie Hirtz

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush Page 2

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush Read online

Page 2

What? Lola hadn’t meant to throw in that ambitious bit about the White House, nor to wrap up the speech abruptly, but the flying spitball had so unnerved her, she leapt into the future, forgetting to fully detail her platform—including her idea for perking up the morning doldrums with five minutes of original riddles each day. Still, the class applauded, cheered, and chanted—with Melanie the loudest of all—“LO-LA, LO-LA, LO-LA, LO…” until the teacher clanged her cowbell and commanded, “Enough hullabaloo in this zoo!”

Amid the cheering and counter-cheering (did Lola hear a few boos?), Buck sauntered over to the podium, flashed his impish grin, and launched into his speech.

“Most of you know me as Buck, Buck-a-roo, the Buckster, the Bucking Bronco…”

Melanie interrupted. “Or Slime Bucket, Bucket of Slime, or just plain Slime.”

“Melanie Papadakis, that’s enough,” snapped the teacher. “One more outburst from you, and you’ll be standing outside with Mr. Hernandez.”

Melanie put her head down, but only for a nod.

Buck continued, “My real name is Charles Wembly the Third. My grandfather, Charles Wembly, donated the designer-colored golf carts for Mirage’s first public golf course. My father, Charles Wembly the Second, paid for the dolphin-shaped buoys at the Mirage swimming pool. I, on the other hand, gave you yo-yos with my face sticker so you wouldn’t get bored in class, and…”

Mrs. Rosenberg drew back—insulted that anyone would find her lectures about ancient history or rare rock collecting boring. Buck’s yo-yos were getting on her last nerves. How many yo-yos had she confiscated the last week? A dozen, at least.

Buck resumed his speech. “I promise to stop hogging the peewee ball at recess, to quit butting in line at lunch, and to cut down on my farting during music.”

Students giggled and pretended to hold their noses.

“When your yo-yo breaks, I’ll buy you a new one,” Buck promised. “Vote for me, pleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeease, and I’ll teach you more yo-yo tricks.” Then Buck went from student to student, hand extended for a hearty shake.

Some students clapped, though others, like Samantha Roberts, rolled their eyes and refused to shake Buck’s slimy hand. Samantha was the smartest student in the class, in the whole world for that matter, but clearly she wasn’t interested in middle school politics. When Lola asked Samantha if she wanted to run for office, Samantha put her hands on her hips and said, “Be serious, Lola. I don’t have time for that. I’m cramming for the Academic Decathlon, and I’ve still got half the estuaries in Africa to memorize.”

Sensing the crowd’s lukewarm response, Buck froze mid-aisle and bellowed, “Vote for me and I’ll take everyone to Laser Lizards.”

The boys, a slim majority of the class, went bonkers, shouting, “All right! Now you’re talking! We’ll vote for you, Buck-a-roo!”

Mrs. Rosenberg tried to quiet the boys’ howling. She clanged the cowbell a dozen times and shouted, “Stop all this hullabaloo!” but Buck’s promise to take the class to Laser Lizards—Mirage’s new game arcade with a virtual Mars landing—had created so much excitement, at least among the boys, that the cowbell was useless.

Half the class never heard their teacher shout, “Bribery is against the election rules. A candidate may not offer goods or services in return for votes.”

Amidst the hooting and “Laser Lizards Now!” chanting, Lola rose to the occasion. She stood on her chair and advised, “Don’t let Slime Bucket buy your vote. Tell him you can’t be bought. Show him you have a spine.”

Melanie, forever loyal to Lola, was the first to reach behind her back and point her thumb at her spine. Lola smiled at Melanie, then stared at the snake in its glass prison.

“There’s more than one snake in this room,” said Lola, throwing her eyes like darts at Buck, then back at Slither. “The difference between this one, Mr. Slither, and that one—Snake-a-roo Buck-a-moo—is that this one doesn’t bite.” Lola, a little carried away with her theatrics, liberated Slither from his prison and draped him around her neck. “I remember when Snake-a-roo Buck-a-moo hoarded all the crayons in kindergarten,” recalled Lola, “and bit anyone who insisted on using red, yellow, blue, green, or any color.” Lola nodded at Melanie, signaling her to point to a tiny scar on her arm.

“Buck bit me on the arm when I was five,” said Melanie, waving her arm, to back up Lola’s story. “Check out the fang marks.”

“Buck did that?” said Lola, making the most out of Melanie’s ancient injury. “How gross.” Then, turning to the snake, she said, “At least this slimy guy doesn’t have fangs.” She kissed Slither’s little head, sending Mrs. Rosenberg into a jaw-dropping tizzy.

“Lola, put Slither back in his house,” said the teacher. “The snake needs a nap and it’s time to vote.”

Lola removed her snake necklace, gingerly placed him back in his prison, and started to sit down when she drew back—noticing something. What was it, ah, yes, a blob, a pink and white rubbery blob with a bulge in the middle, on her chair, awaiting her arrival. It looked like an eyeball. It was an eyeball. A synthetic cow eyeball! Buck, clearly hoping to unnerve her, had left a surprise present—a prop from their science assignment. Lola used a spare tissue to stash the fake eyeball in her desk. She glared at Buck.

Buck, however, was busy digging around in his pockets, looking for something—his cell?—in his baseball jacket. Lola saw Buck take out his smartphone, a banned classroom distraction, and hold it out of sight under his desk, texting someone.

Meanwhile, the election had begun. Mrs. Rosenberg distributed scraps of paper to each member of the class. She asked Samantha Roberts to fetch Hot Dog from outside, where Lola saw him practicing cartwheels in an effort to impress students daydreaming in the classroom across the way. “Remember, this is a secret ballot election,” said Mrs. Rosenberg. “Keep your eyes to yourselves. No wandering snoops.”

Scribbles later, the teacher collected the scraps of paper and placed the secret ballots in a cookie jar. “Samantha,” she said, “please come to the board and help me tally the votes as I read them aloud.”

Samantha strode to the board, where she drew two columns, one for Lola, the other for Buck.

Mrs. Rosenberg opened the first ballot. She squinted, having forgotten her reading glasses—again. “I can’t quite make this out,” she mumbled.

Lola couldn’t stand the suspense, and was about to offer her teacher a magnifying glass when Samantha peered at the note and smiled.

“Lola Zo-o-la,” she read, “you go, girl!”

Mrs. Rosenberg shot Samantha a look. “Pipe down, Samantha. No cheering during vote counting. I will not tolerate any more hullabaloo.”

Melanie, however, cheered with great gusto and encouraged the other girls to join her, shouting “LO-LA-LO-LA-LO-LA-LO-LA!” A chorus of pigtails and ponytails went wild.

Samantha put a mark under Lola’s column on the board.

Mrs. Rosenberg opened the second ballot, tried to hide her disgust, and then nodded first toward Buck, and then Samantha.

One vote for Buck.

The students watched intently, some drummed on their desks, others clenched their teeth. Slither stopped slithering.

Two for Buck.

Two for Lola.

Mrs. Rosenberg continued opening the ballots. Not a chair moved.

Five for Buck.

Five for Lola.

Melanie smiled at her best friend, as if to say, “No matter what happens, I’ve got your back, sister.”

Ten for Buck.

Eleven for Lola!

Lola wished she had a telescope or better yet, an x-ray machine, so she could read the votes before anyone else—and prepare for sweet pickle victory or bitter horseradish defeat. Just as she was straining to see Mrs. Rosenberg’s expression upon reading the next ballot, Lola heard the door open and a voice shout from the back of the room.

“I’m sorry I’m late, son.”

Buck’s father had crashed the election, arrivi

ng unannounced in his pinstriped three-piece designer suit. Charles Wembly II sat down behind Hot Dog’s cowlick, in the back of the room—Spitball Land.

Buck must have texted his father to come to class. Lola had figured that one out, but what she couldn’t understand was how Mr. Wembly, an important businessman who owned Boingo Bits, one of the largest software companies in Mirage, could take off time from work for a measly class election. Then again, Mr. Wembly had never missed one of his son’s Little League games, or passed up a chance to chew out an umpire who said “Strike!” after Buck missed a pitch.

Lola and Buck were tied.

Fifteen votes for Lola; fifteen votes for Buck.

Mr. Wembly rested his jaw on his fist and shook his head in disbelief that his son wasn’t trouncing the competition.

Melanie used American Sign Language to tell Lola, “You’re going to win. I can feel it in the boniest of my bones.”

But Lola wasn’t so sure, as the votes were tallied.

Eighteen votes for Buck; only seventeen votes for Lola.

“Buck-a-roo, you rule!” squealed Hot Dog, jumping on his chair and shooting a fist into the air—perhaps prematurely.

Nineteen votes for Lola; nineteen votes for Buck.

Lola couldn’t imagine sharing the presidency with Buck and his yo-yos, and the pinstriped adult pest in the back of the room.

Only one more ballot remained unopened. Buck gave his dad a thumbs-up.

Slowly, opening the final ballot, Mrs. Rosenberg reminded the class not to boo, sneer, moan, or display any other improper election etiquette. “We can’t all be winners today,” she reminded the class, “though we can be respectful students. Remember, in the end it’s kindness that matters.”

Out of the corner of her eye, Lola saw Buck’s father roll his eyes.

Again, Mrs. Rosenberg squinted, trying to make out the scrawl. Then, hiding her smile, she boomed, “Nineteen votes for Buck. Twenty votes for Lola. Congratulations, Lola Zola. You’re our new class president!”

Lola grinned. Melanie went, “Whoop, whoop!” Samantha high-fived Lola—and girls danced in the aisle.

Buck, however, hung his head—maybe to hide the tears. No more excited thumbs-upping. No more impish grinning. Just bitter disappointment until…

Buck’s father jumped to his feet. “Excuse me, Mrs. Rosenberg, there must be some mistake. I’d like a recount.”

“Mr. Wembly, I really don’t think that’s necessary,” said Mrs. Rosenberg.

“Of course it’s necessary,” said Buck’s father. “I suspect election fraud.”

“Excuse me?” said Mrs. Rosenberg.

Lola, Melanie, and Samantha exchanged looks, as if to say, “No wonder Buck is so messed up. His father is a spoilsport.”

Buck’s father insisted, “I’ll put the ballots back in the cookie jar and read them aloud as you tally up the votes for a second time. I want to inspect them to make sure no one voted twice.”

Lola couldn’t hold back. She popped out of her chair and walked up to Mr. Wembly. “How could I have rigged the vote? We have thirty-nine students in the class and thirty-nine ballots. No one voted twice.” Lola, the mathematician and future lawyer (maybe), beamed proudly.

“I saw you fooling around with something in your desk,” said Mr. Wembly. “You had a funny look on your face, Lola Zola, like you were fishing for something—another piece of paper, a second ballot?”

Lola, whose hand, yes, had crawled back inside her desk, had been attempting to place the jiggley fake cow eyeball inside a baggie. She certainly hadn’t wanted it to contaminate her afternoon carrot snack. Dare she show Mr. Wembly the evidence? Nah. He would merely accuse her of stealing one of the gifted program’s eyeballs in order to one-up the rest of the group. Besides, Lola wanted to get away from this man. He smelled like buckets of cologne and her nostrils itched. Stink City.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Wembly,” said Mrs. Rosenberg, “but the election is over. What’s fair is fair.”

“Don’t talk to me about fairness,” said Buck’s father.”

“What are you talking about?” asked the teacher, incredulous.

“You,” Mr. Wembly said pointing to the teacher, “confiscated his yo-yos.”

Lola looked over at Buck, who was biting his nails down to the cuticles, and for a moment she felt sorry for him. Who would want a father like that?

“I cannot allow a student to buy votes, Mr. Wembly,” said Mrs. Rosenberg.

“Nor, I suppose, can you allow a student’s father to buy the class a new air-conditioning system,” said Buck’s dad, fanning himself to remind Ms. Rosenberg she had complained on more than one scorching occasion about budget cuts robbing her of promised cool air relief.

“That’s right,” said Mrs. Rosenberg, dabbing her upper lip with a tissue. The class might as well have been an oven; she was baking. “New air-conditioning would be nice, but—no.”

Minutes later, still dabbing her upper lip, Mrs. Rosenberg excused the class for lunch. “Be gone, my little Egyptians. Don’t return until you’ve expended every ounce of energy—and are ready to concentrate on Egyptian mummies. No more hullabaloo!”

As Lola and Melanie passed Buck and his father on the way to the cafeteria, they could hear Mr. Wembly scolding Buck.

“Lola beat you in the first-grade thumb-wrestling contest, the second-grade spelling bee, the third-grade skateboarding contest, the fourth-grade ping-pong tournament, and now this?”

“I told you, Dad,” said Buck, his hands deep in his pockets. “She always cheats.”

Lola resisted the urge to shout, “Liar, liar, pants on fire!” Instead, she turned to Melanie and said, “That boy gets on my last nerves.”

“Ignore him, Lola,” advised Melanie. “It’s just a case of sour apples.”

Sour grapes. It was a case of sour grapes. That’s what most people said when they meant someone was jealous. Not Melanie. She always mixed up her adages, but Lola wasn’t about to correct her. That would have been Rudesville.

During lunch, a smug Buck—wearing his baseball cap backwards, hands deep in his pockets—butted in to the cafeteria line, right behind Lola. Smirking, he whispered, “Don’t worry, Lola. It’ll work out.”

“What are you talking about?” asked Lola. “The election?”

“Oh yeah, right,” said Buck, rolling his eyes. “The election and…”

“And what?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing I’m supposed to talk about.”

“Fine,” said Lola. “Don’t talk about it.”

“You’ll find out soon anyway,” said Buck.

“Find out what?” Lola wanted to kick him in the shins.

“Can’t tell you.”

Lola whipped around. She stuck her nose in Buck’s face. “Speak or die.”

Buck sighed. “You mom needs a job, huh?”

“So what.”

“So I heard your dad was making a bunch of lemons at that car plant.”

“Shut up!” said Lola. “My dad made the best cars on earth.”

“Yeah,” said Buck, “and that’s why they’re shutting down the plant.”

Lola fumed. He was getting to her.

“Don’t worry,” said Buck. “My dad’s giving your mom a job.”

“Liar, liar, pants on fire!” This time Lola said it loud enough for everyone at school to hear.

“It’s the truth,” said Buck.

But Lola knew he was lying. Or hoped he was.

“She’s going to be his secretary,” Buck informed.

Secretary? Lola would never again celebrate Secretary’s Day.

As soon as school ended that day, Lola bolted out the classroom door and charged home like a buffalo, praying to the Tumbleweed God, “Make it be a lie, a lie, a lie…”

*** *** ***

Chapter 3

“It’s true, Lola,” said her mother, uncomfortably. “I start work as his administrative assistant

on Monday.” Diane Zola sat at the kitchen table, a whirling fan blowing on her face. She stared at a pile of bills for the gas, the water, the rent, the loan on the new cherry-red Mustang, and more.

“Why didn’t you tell me you were going to work as a servant secretary?” said Lola, furious at having learned the truth from her archenemy at school. Lola looked up at a picture taken the previous Mother’s Day. She and Mom were smiling in the backyard rose garden. Suddenly the vine in the background grew six-inch thorns above Diane Zola’s ears.

“I won’t be a servant,” said Lola’s mom quietly. “And I’m sorry I didn’t tell you earlier. I wasn’t sure how to break it to you. I knew you’d be upset.”

“I’m not upset,” said Lola, steaming. She grabbed a piece of junk mail to rocket into the wastebasket. Bowzer, curled up in a corner of the room, saw the mail fly and pounced on the wastebasket.

“Honey, try not to think about it,” said Mrs. Zola.

“Mommmmmmmmmm! I may be a kid, but I’m not a baby.” Lola’s cheeks turned crimson. “I have a right to know what’s going on and to throw a tantrum if I’m…” Lola searched for the right words to needle her mother. “Pissed off.”

“Lola, I really wish you wouldn’t use such…”

“Pissed, pissed, and double-pissed,” said Lola in defiance.

Diane Zola shuddered at her daughter’s crude expression. “Enough! I was only trying to protect you from…”

“From what?”

“The truth,” said Mrs. Zola. “We’re broke. Like it or not, I have to take that job.”

“You can’t,” said Lola.

“I’m sorry, sweetie.” Diane Zola leaned over to hug her daughter. “We have no choice.”

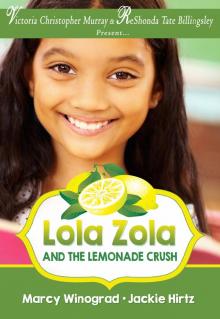

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush

Lola Zola and the Lemonade Crush